by Phyllis Andersen

In the history of gardens, designers, patrons, and owners are often given top billing. Gardeners, especially those in charge of public gardens, are often far less visible. Like theatrical set designers, gardeners are the unseen hands that create and sustain the floral displays so admired by the public. Their workshops are the greenhouses and plant nurseries that grow plants to the stage that they can be added to outdoor displays. Since the late nineteenth-century the gardeners of the Public Garden have sustained a tradition of ornamental planting that delights and educates the public. Visiting the seasonal floral displays are more than a photo op – they are a civic tradition.

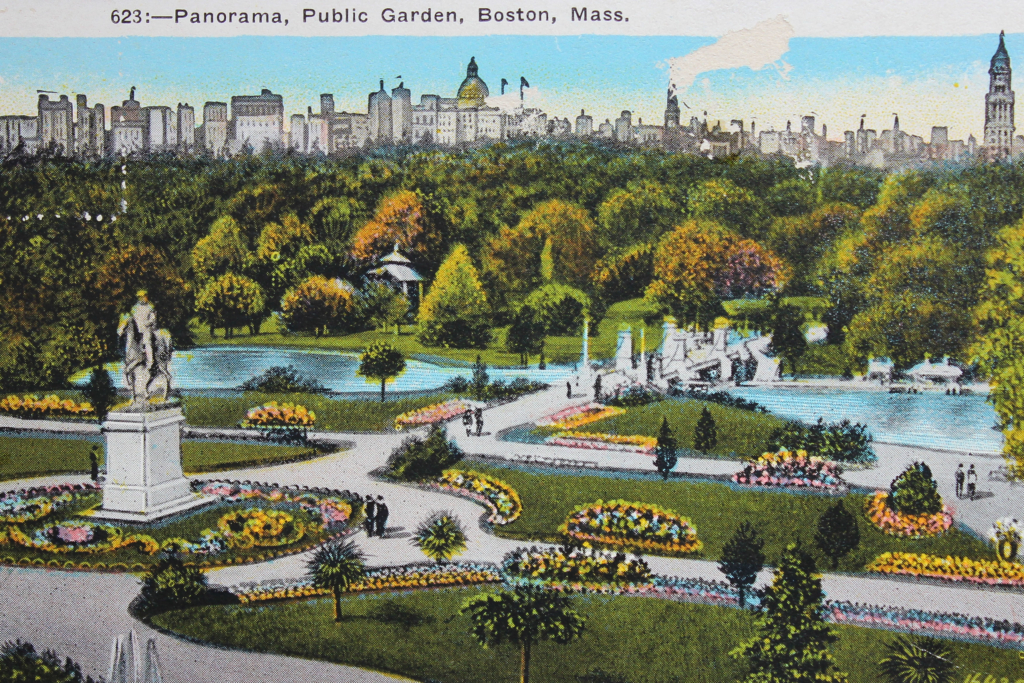

The original design of the Public Garden was the result of an 1859 competition won by George Meacham, then a twenty-five-year old architect with little experience. The Public Garden was his only major landscape project. Meacham’s design was overloaded with features: buildings, greenhouses, arbors, a childrens’ playground, numerous small flower beds as well as trees and shrubs. Cynthia Zaitzevsky, the landscape historian of Boston’s Emerald Necklace park system, notes that “the Meacham plan displays a certain horror vacui” – a desire to fill all twenty-four acres with embellishments. John Galvin, the City Engineer, and James Slade, the City Forester, were charged with constructing Meacham’s plan. They eliminated a significant number of features and reduced the number of ornamental flower beds. Labor costs demanded simplification, but Galvin and Slade were also concerned that the number of formal flower beds would detract from the picturesque winding paths and trees. Today, that tension between the tightly controlled flower beds and the meandering paths and mature trees defines the character of the Public Garden.

The exception to the rule of the unnamed gardener is William Doogue, Superintendent of Common and Public Grounds who oversaw the Public Garden from 1878 to 1906.

Outspoken, media savvy, and politically astute, Doogue was a consummate showman. He courted the press to promote his horticultural extravaganzas and to defy the critics who accused his floral displays of “gaudy” bad taste. Doogue was born in Ireland and studied botany at Trinity College in Hartford. In addition to his work in estate gardens and running his own nursery, Doogue was part of the horticultural team for the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition. Confident of his credentials, Doogue wanted nothing less than to make the Public Garden a show piece of the city. He introduced exotic plants – what the Boston Globe called “tropical glories”: sago palms, crotons, dracaenas, rubber plants, canna lilies, banana plants. He used the technique of theatrical display, arranging plants in a hierarchical manner, like seats in a theatre. He planted roses and other flowering shrubs in vase-like planters along the edge of the lagoon. In 1901 Doogue planted 1500 sea island cotton plants in the area around the statue of George Washington stating that he wanted Boston school children to understand how these plants grow.

Doogue built a number of greenhouses and nurseries around the city to produce plants for the Public Garden and for the other parks and squares under his supervision. One of the largest was in an area known as the Roxbury Canal, now the site of Boston Medical Center. Doogue built greenhouses for wintering over tropical plants, and extensive areas for plant propagation. He was constantly searching for new plants to engage visitors and imported seeds and plants from European nurseries. Doogue described his seasonal plantings to the newspapers in terms of numbers: thousands of bulbs, hundreds of tropicals and rose plants. Doogue was well aware that numbers meant labor and he used this strategy to impress the public and protect his budget.

Doogue died in 1906. His death came just before the creation of the Boston Parks Department in 1913. The new department merged the Board of Park Commissioners with the Department of Common and Public Grounds. Subsequent generations of gardeners worked with less visibility, a more constrained administrative structure, and tighter budget controls. The number of gardeners diminished because of reduced funding but also because mechanization and the availability of labor-saving tools such as reel lawn mowers, pruning tools, and more efficient greenhouse heating systems required fewer staff. Despite this tighter structure the seasonal flower displays prevailed.

Carpet bedding, still a staple of civic planting, was introduced into the Public Garden in the late nineteenth century and continued to be a feature of summer planting until the 1960s. Thousands of small low-growing plants, raised from seed or cuttings in the greenhouses, were transplanted into beds and configured into geometric patterns and images. In 1890 Mayor Thomas Hart instructed the gardeners of the Public Garden to create flower beds in the image of the American flag, the Massachusetts coat of arms, and the seal of the City of Boston. Patriotism in the form of a flower bed! In 1913 John Dillon, the chief gardener of the Public Garden, created a large floral replica of the insignia of the Knights of Columbus, who were having their annual convention in Boston that summer. Commemorating organizations meeting in Boston by creating floral emblems in the Public Garden continued well into the twentieth century, establishing a significant link between City Hall and the Garden. The dual mission of the Public Garden was display and education. In 1933 a large plot near the statue of George Washington featured economic plants such as black pepper, peanuts, pineapple, sugar cane, cocoa trees, avocado, date palms.

Michael Connor joined the Boston Parks Department in 1957 and was Superintendent of Horticulture from 1975 until his retirement in 1999. He continued the floral beds and created award-winning displays at the Massachusetts Flower Show despite a very small staff, a reduced budget, aging infrastructure, Dutch elm disease, and increasing vandalism. It was these conditions that precipitated the forming of the Friends of the Public Garden in 1970. For almost fifty years the Friends has partnered with the Parks Department to protect and maintain the trees, border plantings, and four rose beds in the Garden. As the partnership has evolved, the Friends has assumed a major responsibility for tree and shrub planting. The Friends monitors and treats insect and disease problems and supervises new planting as part of capital projects. The Parks Department continues to create the seasonal floral display.

Roy Blomquist succeeded Connor as Superintendent of Horticulture in 1999. He provided dynamic leadership to the team of gardeners, encouraging advanced training, and strengthening the principles of apprenticeship. Blomquist added new tropical plants to the Garden, new color schemes, and a fresh approach to methods of display. The ornamental beds saw an infusion of new plants: amaranth, cosmos, oleander. Mass planting of canna lilies, a favorite of Mayor Thomas Menino, became an annual feature.

Anthony Hennessey, a close associate of Blomquist, succeeded him as Superintendent and continued the methods of display introduced by Blomquist. Working with Hennessey, Josh Altidor, who came to the Parks Department in 2013 and became Director of Maintenance in 2018, has been the designer of the ornamental flower beds for the past several years. With a sure hand, Altidor has sustained the theatrical staging while introducing new annual plants, many grown from seed. He introduced a modern touch with single color beds, ornamental grasses, and new tropical species. The city-owned greenhouses, now merged into a single facility in Franklin Park, includes areas for plant propagation and house the tropical plants used year after year in the Public Garden and other parks and squares in Boston.

Just as there are remnants of Meacham’s original plan for the Public Garden, the horticultural displays are reminiscent of the design of the late nineteenth-century, interpreted by generations of gardeners devoted to the Public Garden and committed to sustaining its mission as a place to appreciate plants in a unique setting.