Red Admiral Butterfly on Zinnias in the Public Garden

By Christine Helie, Consulting Entomologist, The Growing Tree

Predatory insects perform an integral role in healthy landscapes by keeping pest insects at an acceptable level. However most urban landscapes are out of balance in terms of predators and pests. In these situations it can be helpful to augment the existing population of beneficial insects with those purchased from insectaries, companies that raise natural enemies intended for release.

This year we released 2000 green lacewing larvae throughout the Public Garden, the Boston Common and on the Commonwealth Avenue Mall. Green lacewing larvae (Families: Chrysopidae) resemble alligators in shape and are generalist predators, feeding on many small, soft-bodied insects.

This year we released 2000 green lacewing larvae throughout the Public Garden, the Boston Common and on the Commonwealth Avenue Mall. Green lacewing larvae (Families: Chrysopidae) resemble alligators in shape and are generalist predators, feeding on many small, soft-bodied insects.

Common Prey Includes:

Common Prey Includes:

• Aphids

• Small caterpillars

• Beetles

• Thrips

• Mites

• Whiteflies

• Mealybugs

• Insect eggs

Beneficial insects purchased from insect growers are packaged and shipped overnight for immediate release in gardens, greenhouses, and landscapes. Chrysoperla rufilabris is the green lacewing most often available commercially and is a species regularly observed in our area.

Beneficial insects purchased from insect growers are packaged and shipped overnight for immediate release in gardens, greenhouses, and landscapes. Chrysoperla rufilabris is the green lacewing most often available commercially and is a species regularly observed in our area.

The larvae we received were about 1mm in length and were placed among rice hulls in a ventilated plastic container. For more even distribution, Norm portioned the larvae into smaller cups.

Green lacewings undergo complete metamorphosis and begin life as an egg. Hatching about five days later, larva can consume more than 200 pests each week over their two to three week development. They pupate by creating a cocoon with silken thread and attach themselves to plant material or other structures. After approximately five days in this stage they emerge as adults and the lifecycle begins again.

Green Lacewing adults have pale green bodies, delicate, membranous wings, coppery metallic eyes and long antennae. They feed on pollen, nectar, and honeydew. Honeydew is a sugary liquid excreted by aphids and other insect pests as they feed on plants. It covers the foliage of plants under attack and can often lead to sooty mold problems.

Green Lacewing adults have pale green bodies, delicate, membranous wings, coppery metallic eyes and long antennae. They feed on pollen, nectar, and honeydew. Honeydew is a sugary liquid excreted by aphids and other insect pests as they feed on plants. It covers the foliage of plants under attack and can often lead to sooty mold problems.

However, the presence of honeydew helps adult green lacewing females locate possible sites to lay eggs. Knowing there is a food source available for her brood, adult females will lay eggs at or near areas that are coated with this substance.

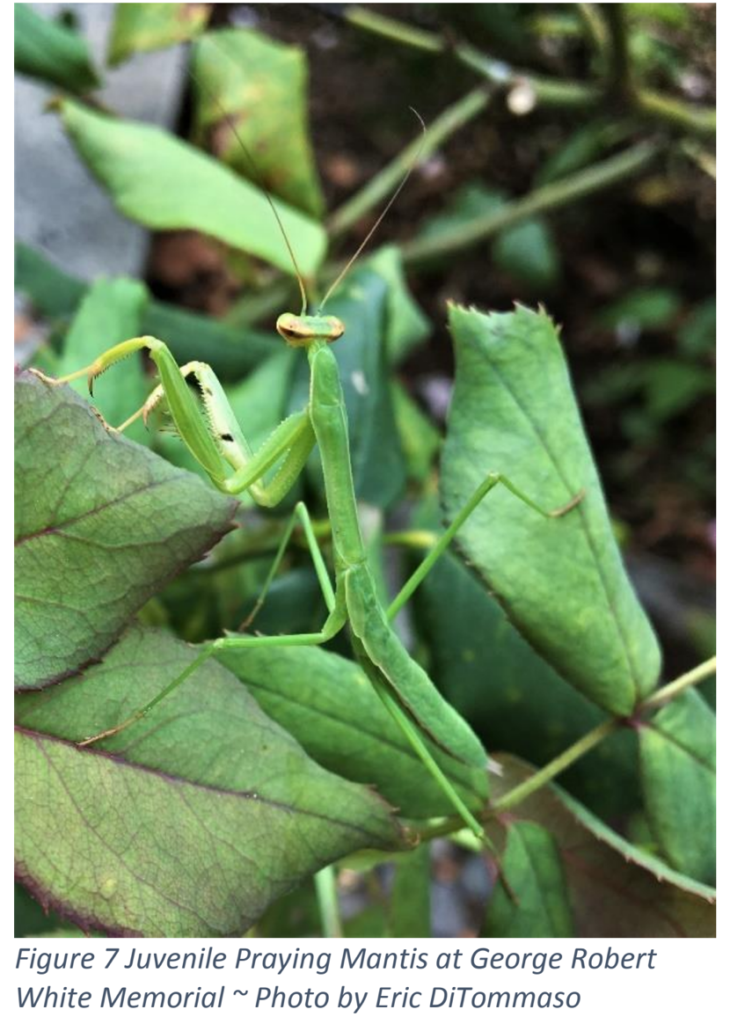

Additionally this year, in the Public Garden, there was a wonderful visit from a praying mantis. In August, while pruning roses in the George Robert White Memorial, Parks Care Specialist, Eric DiTommaso, encountered a young praying mantis who greeted him by walking up his arm. This raised the question of whether the praying mantises we had released in the past were successfully breeding and now living in the parks.

On June 13, 2018 we had released about 100 newly hatched Chinese praying mantises throughout the Public Garden and on the Boston Common. It was quite possible that these mantises had plenty of time to reach adulthood and find a mate. Knowing this, I was determined to find evidence of breeding and started searching for egg cases among the plant material and structures at the George Robert White Memorial.

Thick foliage at this time made this task difficult. However, Normand informed me that the Matthew R Foti Landscape & Tree Service crew was going to be pruning the border plants near the memorial fountain in the next few weeks. Using this opportunity, I gave him a spent egg case (ootheca) specimen from my collection to show the crew and encourage them to look for one while they were pruning.

Thick foliage at this time made this task difficult. However, Normand informed me that the Matthew R Foti Landscape & Tree Service crew was going to be pruning the border plants near the memorial fountain in the next few weeks. Using this opportunity, I gave him a spent egg case (ootheca) specimen from my collection to show the crew and encourage them to look for one while they were pruning.

They were very enthusiastic about this quest and our educational moment paid off as they did discover one ootheca among the privet hedge. It was exciting to think that the juvenile mantis that Eric met could very well be one from our family of praying mantises. Supporting populations of natural enemies or using them to suppress harmful insects is a necessary strategy in any integrated pest management program (IPM).

They were very enthusiastic about this quest and our educational moment paid off as they did discover one ootheca among the privet hedge. It was exciting to think that the juvenile mantis that Eric met could very well be one from our family of praying mantises. Supporting populations of natural enemies or using them to suppress harmful insects is a necessary strategy in any integrated pest management program (IPM).

Conserving beneficial insects in our parks should be our ultimate goal. This requires that we recognize existing beneficial insects, provide suitable habitats for them to complete their individual lifecycles, and manage these habitats to minimize harm to them.

Conserving beneficial insects in our parks should be our ultimate goal. This requires that we recognize existing beneficial insects, provide suitable habitats for them to complete their individual lifecycles, and manage these habitats to minimize harm to them.