THE COMMON

“The Embrace,” a memorial honoring Dr. Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King, located near Parkman Bandstand

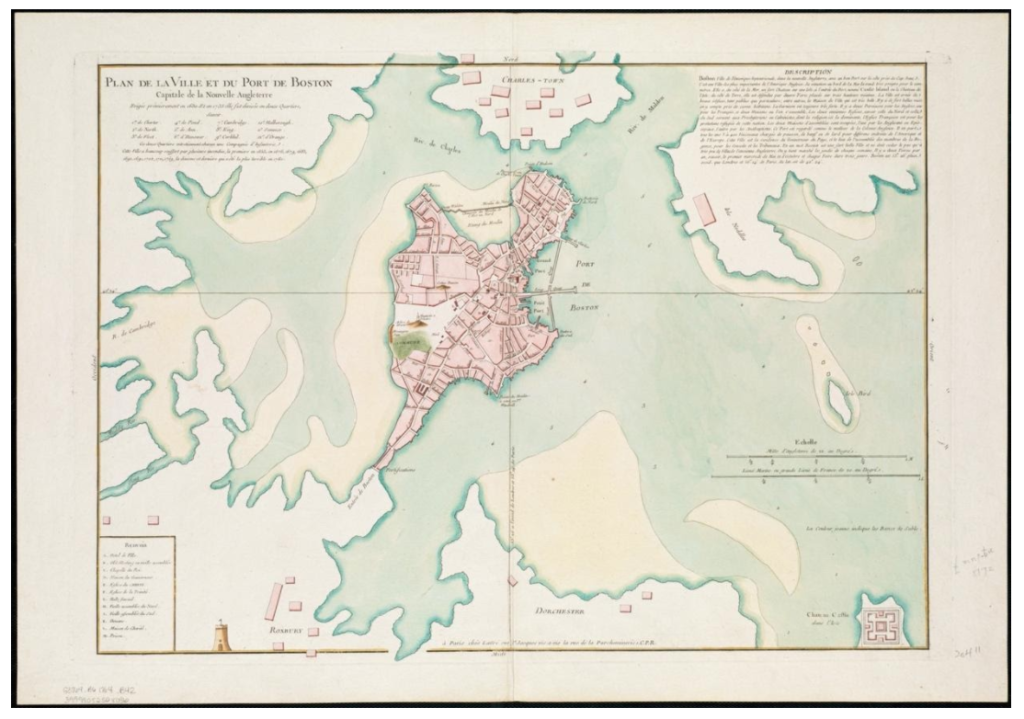

The Boston Common, founded in 1634, is the oldest public park in America. Its fifty acres form a pentagon bounded by Tremont, Park, Beacon, Charles, and Boylston Streets. The Common attracts millions of people every year, both residents and visitors. A visitor information center for all of Boston is located on the Tremont Street side of the park.

From Colonial times to the present day, the Common has been at the center stage of American history. It has witnessed executions, sermons, protests, and celebrations, and it has hosted famous visitors from Generals Washington and Lafayette to Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. and Pope John Paul II. In Colonial times, it served as a meeting place, pasture, and military training field. Bostonians in the nineteenth century added tree-lined malls and paths and, following the Civil War, monuments, and fountains. The twentieth century saw victory gardens, troop entertainment, rallies for civil rights and against the Vietnam War, and the first papal mass in North America.

Today, the Common is the scene of sports, protests, and events large and small. Yet for all its adaptation to modern life, the Common remains a green retreat remindful of its storied past.

Brewer Fountain Plaza

Brewer Fountain Plaza is a popular destination on the Boston Common. The Friends of the Public Garden is excited to announce that from April through October, Plaza visitors can enjoy a rotating food truck program and other plaza programming at the Plaza on Boston Common (near Park Street Station). Learn more.

Frog Pond

The Frog Pond is the heart of the Common all year round. In summer, it provides an escape from the heat and a great spot for a picnic. Children from all over the city squeal and splash in the spray pool, while grown-ups wade in or watch from the grassy slopes. Learn more.

Common Canine

The Common Canine program, developed by the Friends of the Public Garden, provides a meaningful recreation for dogs on Boston Common, protects turf and plantings from overuse, and minimizes interference with other users’ quiet enjoyment of the park. Learn more.

HISTORY OF THE COMMON

The land of Boston Common is the unceded territory of the Massachusett Nation. The Confederation of Indigenous Massachusett lived and thrived for hundreds of generations on the land, marshlands, and waterways now known as Boston. Long before 1620, European trading ships traveled throughout New England trading goods with the Indigenous tribes. The Europeans brought diseases that were deadly to the Indigenous people, and plagues traveled throughout the region devastating the tribes and dramatically reducing their numbers. Just as the Massachusett population began to recover, the English settlers arrived in the 17th century.

We acknowledge that our parks occupy what was the unceded land, marshlands, and waterways of the Massachusett Nation, today known as Boston. We acknowledge the painful history of forced removal of Indigenous peoples from their land, and that the work of repair is ongoing. In the spirit of the Massachusett people past, present and future, we acknowledge that we live in a bond of reciprocity with the plant and animal relatives who call our parks home. We honor the gifts given to us by this land and return them with our care.

The original Common was gently rolling scrubland, sloping gradually from Beacon Hill to the tidal marshes of Back Bay. The original water line roughly followed today’s Charles Street. It was only lightly wooded, with perhaps three trees of notable size, including the legendary “Great Elm.” Of the four original hills and three ponds, only Flagstaff Hill and the Frog Pond are now discernible.

The seventeenth-century Common, rough and rural, was well suited as a pasture, its primary purpose. The village herd of seventy milk cows grazed peacefully, watched over by a town-appointed keeper. The Common was also a frequent site for hangings and other forms of execution of murderers, thieves, deserters, pirates, “witches,” and religious dissenters, especially Quakers.

In an age of optimism and public display, the nineteenth-century Common played host to an extraordinary chronicle of events, both serious and fanciful, including balloon ascensions and early football. During the Civil War, the Common witnessed antislavery protests, recruitment rallies, a wild victory celebration, and then a mass demonstration of grief at the death of President Lincoln.

By the 1970s the Common had suffered from many years of neglect, with half of its trees lost, the Frog Pond empty, fountains defunct, fencing removed, and a grave imbalance of use and care. In recent decades, public-private efforts have brought notable improvements including new fencing, a refurbished playground and bandstand, a rejuvenated Frog Pond with an artificial ice rink, a management plan for future maintenance and control, and restoration of the Brewer Fountain.

Today, the historic Boston Common attracts millions of people every year, both residents and visitors. It is a place of sports, informal and organized; exhibitions; musical events; a Shakespeare festival; rallies and protests; charity walks and art shows; and on New Year’s Eve, the fireworks of Boston’s famous First Night. Once a year, in long custom, the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, formed in 1638, marches again before the dignitaries of the day.

SCULPTURE AND MEMORIALS

The first piece of public art arrived on the Common in 1868. Named after its donor, Gardner Brewer, the Brewer Fountain is a bronze copy of a French original that won a gold medal at the 1855 Paris World’s Fair. Brewer, a wealthy Boston merchant, purchased a direct cast of the original in France and had it installed within sight of his Beacon Street house. Its sculptures represent mythological figures associated with water: Neptune, Amphitrite, Acis, and Galatea. It was later moved to its present location near the Tremont Street Mall. Waterless for many years, the fountain was recently restored to its former glory.

Designed by architect/sculptor Martin Milmore, the neoclassical Soldiers and Sailors Monument, on top of Flagstaff Hill, is a Civil War memorial in the form of a victory column. At its dedication in 1877, Generals McClellan and Hooker were among those attending, along with two Confederate officers. From colonial to modern times, the hill has been a favorite sledding place for children.

In 1888 the Boston Massacre Memorial was dedicated near the Tremont Street Mall. The work of Robert Kraus, its standing bronze figure represents Revolution breaking the chains of tyranny. The bas-relief depicting the events before the Old State House on March 5, 1770, features Crispus Attucks, the first to fall.

The most acclaimed piece of sculpture on the Common is Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial, located opposite the State House. Saint-Gaudens was the foremost American sculptor of his day. After accepting the Shaw Memorial commission in 1884, he took almost fourteen years to complete the job. The enormous bas-relief depicts the mounted Colonel Robert Gould Shaw leading the Massachusetts 54th Regiment, the first all-volunteer black regiment in the Union army. Colonel Shaw, together with many of his men, died at Fort Wagner, South Carolina, in July 1863.

The monument was finally unveiled on May 30, 1897, with ceremonies lasting most of the day. The military parade included some old soldiers who had left for war from that very spot. In 1982, the Friends of the Public Garden raised funds to restore and endow the monument, which was rededicated in 1997 with General Colin Powell in attendance.

The Parkman Bandstand, in the form of a Greek temple, was dedicated in 1912. It honors the Common’s first and greatest benefactor, George Francis Parkman (1823-1908), who bequeathed $5 million for the care of the Common and other city parks. Designed for concerts, the bandstand also gave the Common its most useful forum for public speaking. Restored in 1996, it has served as the backdrop for the annual Shakespeare on the Common productions, along with other events.

In 1930, as part of Boston’s 300th anniversary celebration, the Founders Memorial was erected along Beacon Mall on the Common. Its bronze bas-relief, sitting in a large frame, shows William Blackstone welcoming John Winthrop’s party to Shawmut peninsula, as allegorical figures look on. The reverse side of the monument, facing Beacon Street, is inscribed with quotations from John Winthrop and William Bradford.

The Parkman Plaza, a circular paved area located in front of the Visitors’ Center, also honors the Common’s great benefactor George Francis Parkman. It was designed by Shurcliff & Merrill and dedicated in 1960. The three bronze statues representing Industry, Religion, and Learning are the work of Arcangelo Cascieri and Adio diBiccari.