The Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial restoration is now complete. The Partnership to Renew the Memorial has created a model for the nation for the use of a preservation and restoration project to be a catalyst for a broad conversation on race, equity, and social justice. The heroes of the glorious 54th inspired us to move forward, just as they proclaimed as they headed into battle: Forward 54th Forward.

Please sign the digital Witness to History book to commemorate

the unveiling of the completed Robert Gould Shaw and

Massachusetts 54th Regiment restoration project.

FACES OF THE 54TH: ONLINE DATABASE – ARE YOU A DESCENDANT?

The National Park Service has compiled an online database of the 54th Regiment soldiers and officers as part of their “Faces of the 54th” project. View the database here. If you are a descendant of the Shaw Mass. 54th Regiment, fill out the form here. Read the Bay State Banner article about the project.

ABOUT THE PROJECT

The work began in the summer of 2020, and was initially planned to take 5-6 months. Due to a combination of factors, including the COVID pandemic, the restoration project ended up taking over a year and a half to complete. All of the bronze and stone was removed from the plaza level up, taken offsite to two different conservation studios, with the bronze bas-relief meticulously restored locally. New waterproofing was installed under the plaza’s brick, and a new concrete foundation has been built under the bronze, and everything replaced, pinning the bronze to the marble structure that surrounds it. Also,the team installed a new stainless-steel frame between the bronze and the marble, designed to stabilize the entire monument.

The plaza substructure has been protected by installing a system called “cathodic protection” into the concrete under the plaza. This protects the steel support beams from corrosion by introducing another metal known as sacrificial. Through the use of an electrical current, the corrosion is drawn to the sacrificial metal instead of the steel beams.

APRIL 15, 2021: The restoration of the Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial is now 90% complete. Perhaps the most essential – and least visible – portion of the project has reached a critical point. The dramatic return of the bronze bas-relief was well documented last month, but the actual foundation of the monument is at the heart of the restoration efforts. The (stone) eagles have landed! The remaining units of Tennessee marble, waiting to be positioned, will complete the stone surround. The stainless-steel frame that was fabricated to stabilize the Memorial, in case of any future seismic activity, has been secured to the back of the bronze and the new concrete foundation on which it sits. After the remaining pieces of marble are positioned around this new frame, the project will move into its final phase. There is much more left to do, including the reinstallation of the marble seating units, the brick pavers on the plaza, and the finish pointing of all mortar joints.

MARCH 03, 2021: Today the bronze bas-relief was positioned on its new structural concrete plinth so the reassembly of the remaining Tennessee marble surround can be put into place. The transportation protection will be removed over the next few days but the bronze will remain protected for the duration of the project except at times the bronze conservator is working on the bas-reliefs final touch-ups.

FEBRUARY 02, 2021: At the Shaw 54th construction site, the rebuild continues under a temperature-controlled tented condition. The heated tent around the site was added to support winter work and required special field and scheduling coordination. The bronze bas-relief is undergoing the last of the conservation process at Skylight Studios. Once complete, the bronze will be crated for travel and stored until its return to the Boston Common. Recently, the new concrete plinth was poured and the Tennessee marble balustrade units were reset. Many more carefully sequenced steps are needed before the bronze returns and the McKim design once again merges with the Saint-Gaudens bronze. The final construction steps are sensitive to weather conditions, but a new construction schedule is being reviewed now with an eye toward a spring completion date. Look for an updated completion schedule to be announced soon.

DECEMBER 01, 2020: With winter approaching, the interpretive signage surrounding the restoration site has been temporarily moved inside and will be reinstalled in the spring.

NOVEMBER 21, 2020: Conservators at Skylight Studios in Woburn continue their efforts restoring the bronze bas relief, and the stone conservators in Lenox, MA are working on the conservation of the granite and marble that surround the Memorial. We expect the project to last into the spring of 2021.

SEPTEMBER 22, 2020: The bronze bas relief is currently being conserved at Skylight Studios in Woburn. Read the Boston Globe feature here.

AUGUST 17, 2020: The hoisting of the bronze bas-relief dramatically took place. The bronze was lifted off its base and brought safely down to rest on Beacon Street Mall before being placed on a flatbed truck for the successful transport to Woburn early Tuesday, August 18, 2020. View photos here.

AUGUST 14, 2020: The steel support structure, or “shark cage” has been completed around the memorial. Next up, wood support structures will be built around the “cage” that will limit the movement of the bronze during transportation to the conservator’s studio in Woburn, MA.

AUGUST 06, 2020: Removal of the stone surround at the Shaw 54th Memorial continues. The blue tape indicates the granite units that are recommended to be removed and reset. Everything will be restored offsite and returned in the fall.

JULY 17, 2020: The construction company is removing the coping stones, the pieces of marble that form the top of the Memorial. They will be crated and taken to the conservation facility.

JULY 08, 2020: The plaza balustrade sections of the Memorial are being removed and placed into wooden crates for transport to the conservation facility.

JULY 01, 2020: 900 feet of interpretive signage is being installed along the construction fencing, revealing the story of the Civil War, the 54th Regiment, and the Memorial that commemorates it. Installation of the interpretive signage – a museum without walls for all to engage with and enjoy – will be completed by week’s end and remain in place through the completion of the restoration process.

JUNE 23, 2020: Shoring of the monument, stone removal preparation (including mortar joint cutting and stone cleaning method mockups) will continue for the next several weeks, led by Louis C. Allegrone Construction with support from design consultant Silman Structural Engineers. Starting in July, the bronze and stone will be removed from the plaza level up and taken offsite for conservation.

Private funds built the Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial, which was given to the City of Boston on May 31, 1897. By the late 20th century, after decades of neglect, the Memorial was in extremely poor condition, a victim of corrosion and vandalism. In 1981, the Friends of the Public Garden convened the Committee to Save the Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial and led a campaign to raise over $200,000 for the monument’s restoration and to establish an endowment for its care. The Friends has been caring for it ever since.

In 2015, while working on the Memorial, stone conservators inform the Friends that the monument’s brick core has become deteriorated from water penetration over time, making it vulnerable to seismic events. An engineering study is conducted, leading to a $2.8 project to reconstruct and stabilize the Memorial. The National Park Service joins the Friends and City of Boston in the work, successfully securing 50% of the funding through the national Helium Fund and becomes the lead partner – a requirement for use of Helium Act funds. The City and the Friends provide the other 50%, supported by a generous grant from the Harold Whitworth Pierce Charitable Trust.

The Committee to Renew the Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial

Co-Chairs

Charlie Baker Governor, Commonwealth of Massachusetts

Robert Stanton Former and first African American Director, National Park Service

Martin J. Walsh Co-chair Emeritus, former Mayor of Boston, US Secretary of Labor

Michelle Wu Mayor of Boston

Committee Members

Catherine Allgor President, Massachusetts Historical Society

Renée Ater Provost Visiting Professor, Brown University

Martin Blatt Civil War Historian; Professor, Northeastern University

David Blight Professor of American History, Yale University, Director, Gilder Lehman Center

Andrea Campell Former Boston City Council President

Colin “Topper” Carew Director, Code Next; Visiting Scholar, MIT

Adelaide Cromwell Historian; Co-Founder of the Department of African Studies, Boston University

Drew Faust Civil War Historian and President Emerita, Harvard University

Bernie Fulp President, GoBiz Solutions, Inc.

Carol Fulp Chief Executive Officer, Fulp Diversity LLC

Henry Louis Gates Professor and Director, Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, Harvard University

David Hencke U.S. Army (Ret.), Executive Officer, 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment

Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham Professor of History and of African and African American Studies & Chair, Department of History, Harvard University

Kim Janey, Former Mayor of Boston

Paula Johnson President, Wellesley College

Rick Kendall Superintendent, Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site

Ted Landsmark Professor and Director of Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy, Northeastern University

Cheryl LaRoche Department of American Studies, University of Maryland

Henry Lee President Emeritus, Friends of the Public Garden

Brent Leggs Director, African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, National Trust for Historic Places

David McCullough Pulitzer Prize Recipient; Historian, Author, Narrator

Robert Minturn Shaw descendant who donated Shaw’s sword to the Massachusetts Historical Society

Frank Moran Representative and Chair, Massachusetts Black and Latino Political Caucus

Beverly Morgan-Welch Associate Director for External Affairs, National Museum of African American History & Culture, Smithsonian Institution

Lee Pelton CEO & President, The Boston Foundation

Colette Phillips President & CEO, Colette Phillips Communications

Harold I. Pratt Founder and Partner, Nichols and Pratt, LLP

Byron Rushing Former Massachusetts State Representative

Sarah-Ann Shaw Retired WBZ-TV Reporter

Frank Smith Founding Director, African American Civil War Museum

John Stauffer Professor of English and of African and African American Studies, Harvard University

Steve Tompkins Suffolk County Sheriff

Col. Dana Sanders-Udo Commander, 54th Mass Volunteer Regiment and Chief of Diversity and Inclusion, Massachusetts Army National Guard.

Edith Walker Descendant of John J. Smith, famed abolitionist and Massachusetts State Representative

Liz Walker Retired Pastor, Roxbury Presbyterian Church

Karen Holmes Ward Director of Public Affairs and Community Services, WCVB-TV

Benny White* President, 54th Massachusetts Regiment, Company A

Linda Whitlock Founder and Principal, The Whitlock Group

Mary Minturn Wood Shaw descendant who donated Shaw’s sword to the Massachusetts Historical Society

Steven Wright Partner, Holland and Knight

* Deceased

ArtsEmerson

Beacon Hill Scholars

Boston African American National Historic Site/National Park Service

Boston Athenaeum

Boston Children’s Chorus

Boston College

Boston University

Bunker Hill Community College

Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice | Harvard University

Community Change, Inc.

Concerned Black Men of Massachusetts, Inc.

Elma Lewis Center for Civic Engagement, Learning, and Research | Emerson College

Dillaway-Thomas House

Facing History and Ourselves

Historic Boston

Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground | Boston University

Hyde Park Historical Society

John Craig Freeman, Emerson College

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Economic Justice

Massachusetts Black and Latino Legislative Caucus

Massachusetts Historical Society

MassVote

Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists

NAACP Boston Chapter

National Voting Rights Museum

New Democracy Coalition

NAACP New England Area Conference

Northeastern University/Northeastern Crossing

Portraits of Purpose Initiative

Royall House and Slave Quarters

Roxbury Community College

Roxbury Cultural District

Roxbury Historical Society

Suffolk University

Urban League of Eastern Massachusetts

Vilna Shul

William Monroe Trotter Institute at UMass Boston

The iconic bronze bas relief of the Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial is back on the Boston Common and open to the public. Read coverage in the Boston Globe, Associated Press, WCVB, and Boston Herald for an in-depth look at the Memorial’s return to the Common.

The press release was posted to the State House News Service website and North End Waterfront News, as well as on the Boston and Beacon Hill Patch sites.

The bronze conservation was featured on the front page of the September 23, 2020 edition of The Boston Globe. Read the full article here.

Stories appeared in the Boston Globe Metro Section, the Boston Herald, MSN, and in the Boston Business Journal’s “5 Things to Know Today” Newsletter for Memorial Day.

Friends of the Public Garden President Liz Vizza was interviewed by three television news stations for weekend coverage on WCVB 5, Black News Channel, and WBZ-TV 4 for their online streaming service – which all ran on Memorial Day 2020. There was an article in the Beacon Hill Times.

Liz Vizza from the Friends, and the Director of Education and Interpretation at the Museum of African American History, L’Merchie Frazier were interviewed again by WBZ-TV 4 with on-the-ground footage of the Restoration.

A vacant plot of land in Hyde Park is the location where the 54th Regiment camped before going south to fight in 1861. Today, a development proposal is in place to build townhomes on the land; some are fighting to preserve it.

MAY 31, 2021: “How Black Civil War Veterans Inspired The Very First Memorial Day,” WGBH

MAY 30, 2021: “Shaw 54th Massachusetts Regiment Memorial ceremonial unveiling event on Memorial Day,” Boston Herald

MAY 28, 2021: “Monument honoring Black Civil War unit back on full display,” AP

MAY 28, 2021: “Shaw Memorial Honoring Black Union Army Soldiers Unveiled After A Year-Long Restoration Project (Liz Vizza Interview),” WBUR

MAY 27, 2021: “Memorial honoring bravery of 54th Regiment returns to Boston Common (Liz Vizza Interview),” WCVB

MAY 26, 2021: “Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial to reopen Friday on Boston Common,” Boston Globe

MARCH 3, 2021: “Black soldiers monument returns after $3M restoration (Interview with Leslie Adam),” WCVB-5

MARCH 3, 2021: “Black soldiers monument returns to Boston Common after $3M restoration,” Boston 25 News

MARCH 3, 2021: “Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial returns to the Boston Common,” Boston Herald

MARCH 3, 2021: “Civil War memorial to 54th Regiment returns to Boston Common,” Boston Globe

MARCH 3, 2021: “Black soldiers monument returns after $3M restoration,” AP

FEBRUARY 24, 2021: “Boston restores monument to Black Civil War troops,” PBS News Hour

MAY 26, 2020: “Shaw 54th regiment memorial work underway at Boston Common,” Boston Herald

MAY 25, 2020: “$2.8 million restoration of Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial underway in Boston,” WCVB

MAY 25, 2020: “Shaw 54th Memorial restoration project readies For construction on Boston Common,” North End Waterfront News

MAY 22, 2020: “Renovations Start on Civil War Memorial honoring the Massachusetts 54th Regiment,” Boston Globe

OCTOBER 15, 2019: “Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial to Undergo Multi-Million Dollar Restoration,” NBC

OCTOBER 15, 2019: “Shaw 54th Regiment memorial to be restored, repaired,” Boston Herald

OCTOBER, 2019: “Shaw 54th Memorial getting $2.8M facelift,” WCVB

OCTOBER 15, 2019: “Civil War memorial across from State House will be taken down for major face lift,” Boston Globe

SEPTEMBER 4, 2019: “Public Garden’s Robert Gould Shaw memorial slated for restoration,” Bay State Banner

SEPTEMBER 21, 2018: “Revisiting and Reliving the History of the Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial,” WGBH

AUGUST 16, 2018: “Restoring the Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial,” The Bay State Banner

JULY 30, 2018: “Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial to undergo major restoration,” Curbed Boston

JULY 27, 2018: “Facelift for Civil War memorial on Common to spark talks on race,” The Boston Globe

JULY 27, 2018: “Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial To Undergo Restoration,” The ARTery, WBUR

PAST EVENTS

MARCH 30, 2021: Allyship and the Mass. 54th: Advancing Our Journey to an Antiracist America Stream on Facebook.

OCTOBER 23, 2020: A Community Conversation: Voting Rights and the Perilous March to Freedom. Stream on Facebook.

AUGUST 24, 2020: A Community Conversation: The Power of Public Monuments in a Time of Racial Reckoning. Stream on Facebook.

JUNE 19, 2020: Poetry as Protest: A Night of Poetry & Conversation with Dr. Malcolm Tariq. View information here.

OCTOBER 15, 2019: The Shaw 54th: Restoring the Memorial and the Dialogue on Race. View information here.

JANUARY 9, 2019: A Community Conversation: The Power of Public Monuments and Why They Matter. View information here. Stream below via ![]()

JULY 17, 2018: Launch of the Shaw/MA 54th Regiment Memorial Restoration Project. View information here.

AR EXPERIENCE

We’re excited to partner with Hoverlay to create an Augmented Reality experience, which brings the Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial, Boston’s most iconic work of public art, right into your living room.

We’re excited to partner with Hoverlay to create an Augmented Reality experience, which brings the Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial, Boston’s most iconic work of public art, right into your living room.

This Augmented Reality experience is available to anyone at home, using your phone, on the Hoverlay app. Search for the Shaw54MemorialAtHome channel or this direct link from your mobile device.

We are excited to partner with EarthCam to provide a photo time-lapse of the restoration process. Please check back later for a video.

PARTNERS

MORE ABOUT THE SHAW 54th REGIMENT MEMORIAL AND BOSTON’S FREE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY

HISTORY OF THE SHAW 54th REGIMENT MEMORIAL

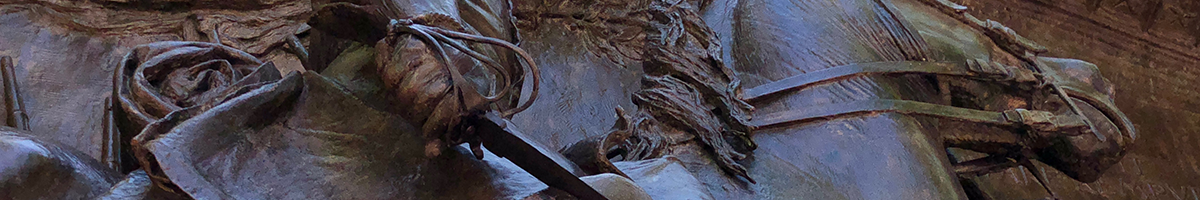

The most acclaimed piece of sculpture on Boston Common is the Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial by Augustus Saint-Gaudens; a memorial to that group of men who were among the first African Americans to fight in the Civil War. The monument portrays Shaw and his men marching down Beacon Street past the State House on May 28, 1863 as they left Boston on their way to South Carolina, Shaw erect on his horse, the men marching alongside.

The most acclaimed piece of sculpture on Boston Common is the Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial by Augustus Saint-Gaudens; a memorial to that group of men who were among the first African Americans to fight in the Civil War. The monument portrays Shaw and his men marching down Beacon Street past the State House on May 28, 1863 as they left Boston on their way to South Carolina, Shaw erect on his horse, the men marching alongside.

Shaw and his men were among the units chosen to lead the assault on the Confederate Fort Wagner, part of the Charleston defenses. In the face of fierce Confederate fire, Shaw led his men into battle by shouting, “Forward, Fifty-Fourth, forward!”. In brutal hand-to-hand combat, Shaw was shot through the chest and died almost instantly; 281 members of his soldiers (almost half of the regiment) were killed, wounded or captured.

Soon after the tragic events at Fort Wagner, on July 18, 1863, the survivors of the first all volunteer black regiment in the Union Army raised funds for a memorial on Morris Island, South Carolina, but it was never built. In 1865 Joshua B. Smith, an African-American businessman and Massachusetts state senator, once an employee of the Shaw family, raised funds with the Black community on Beacon Hill and led the first movement to erect a monument to Colonel Shaw in Boston. An executive committee was formed, intending “not only to mark the public gratitude to the fallen hero, who at a critical moment assumed a perilous responsibility, but also to commemorate the great event, wherein he was a leader, by which the title of colored men as citizen soldiers was fixed beyond recall.”

![]() Boston African American National Historic Site: A Brave Black Regiment

Boston African American National Historic Site: A Brave Black Regiment

![]() See the Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial featured in PBS: 10 Monuments That Changed America (at the 15:23 mark)

See the Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial featured in PBS: 10 Monuments That Changed America (at the 15:23 mark)

With the deaths of Governor Andrew and Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, the chief political supporters of the memorial effort, the project languished until the early 1880s. Augustus Saint-Gaudens, whose newly completed Farragut Monument in New York City had received great praise, was then introduced to the executive committee members by the well-established Boston architect H. H. Richardson. Saint-Gaudens was one of the premier artists of his day; he grew up in New York and Boston, and trained in Paris. The sculptor began work immediately on a design. By the end of 1883 he had produced numerous drawings and several small models of the proposed relief. The committee approved and a contract was signed on February 23, 1884, specifying a modest bronze relief to be completed in two years. Richardson was the original choice as architect for the project, but he died and was succeeded by Charles McKim, of the noted New York firm of McKim, Mead and White, who designed the frame and the terrace. The committee originally had proposed a free-standing equestrian statue, but Shaw’s family believed that type of monument should be reserved for heroes of a higher military rank than their young son. Saint-Gaudens, accordingly, “fell upon the plan of associating him directly with his troops in a bas-relief, and thereby reducing his importance.”

With the deaths of Governor Andrew and Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, the chief political supporters of the memorial effort, the project languished until the early 1880s. Augustus Saint-Gaudens, whose newly completed Farragut Monument in New York City had received great praise, was then introduced to the executive committee members by the well-established Boston architect H. H. Richardson. Saint-Gaudens was one of the premier artists of his day; he grew up in New York and Boston, and trained in Paris. The sculptor began work immediately on a design. By the end of 1883 he had produced numerous drawings and several small models of the proposed relief. The committee approved and a contract was signed on February 23, 1884, specifying a modest bronze relief to be completed in two years. Richardson was the original choice as architect for the project, but he died and was succeeded by Charles McKim, of the noted New York firm of McKim, Mead and White, who designed the frame and the terrace. The committee originally had proposed a free-standing equestrian statue, but Shaw’s family believed that type of monument should be reserved for heroes of a higher military rank than their young son. Saint-Gaudens, accordingly, “fell upon the plan of associating him directly with his troops in a bas-relief, and thereby reducing his importance.”

The commissioners became increasingly restless as Saint-Gaudens completed numerous other projects while the Shaw remained unfinished. The committee became very impatient, and threatened to fire Saint-Gaudens and hire sculptor Daniel Chester French. Saint-Gaudens continued work on the memorial. He had African American men pose in his studio and modeled 40 different heads to use as studies. His concern for accuracy also extended to the clothing and accoutrements. This is the first time African American people were depicted as individuals, not stereotypes, and the first piece of sculpture to memorialize black men. It shows the young Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, known to Saint-Gaudens through photographs, astride his horse with an absolutely erect posture with the men of the 54th marching alongside. It took Saint-Gaudens fourteen years to complete the memorial, but its greatness was recognized immediately. What started as a conventional relief eventually grew into an artistically challenging project of immense psychological and physical proportions. The sculptor later explained, “In justice to myself I must say here that from the low-relief I proposed making when I undertook the Shaw commission, a relief that reasonably could be finished for the limited sum at the command of the committee, I, through my extreme interest in it and its opportunity, increased the conception until the rider grew almost to a statue in the round and the negroes assumed far more importance than I had originally intended…thus, the memorial continued to evolve for another twelve years.”

In the memorial’s background, Shaw’s father suggested using the motto of the Society of the Cincinnati, an organization formed after the Revolutionary War for officers and their descendants, and of which Robert Gould Shaw was a hereditary member. The motto, OMNIA

RELINQVIT SERVARE REMPVBLICAM (He forsook all to preserve the public weal), was used. Among other symbolic details are 34 stars along the top, representing the states of the Union in 1863. The 11 x 14 foot bronze bas-relief was cast by the Gorham Manufacturing Company, and placed in an architectural setting designed by Charles McKim.

The Shaw MA 54th Memorial remains one of sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ most stirring and celebrated masterpieces and is considered by some to be America’s greatest public monument. Private funds built this monument, presented to the City of Boston on May 31, 1897 as a reminder to future generations of the “pride, courage and devotion” of the men it honors. The Friends of the Public Garden raised funds to restore and endow the monument in 1982 and memorialized the fallen soldiers by adding their names on the rear of the monument under Proverbs 10:7 “Memory of the Just is Blessed”, fulfilling an original request by the Shaw family.

54TH MASSACHUSETTS VOLUNTEER INFANTRY REGIMENT

From the beginning of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln argued that Union forces were not fighting to end slavery but to prevent the disintegration of the United States. For abolitionists, however, ending slavery was the reason for the war, and they argued that African Americans should be able to join the fight for their freedom. On January 1, 1863, amidst the tumult of the war, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, providing freedom for persons enslaved in the states in rebellion and the impetus for black men to serve in the military.

The presidential order came at a time when state governors were responsible for raising regiments for federal service. Early in 1863, Abolitionist Governor John Albion Andrew of Massachusetts issued the Civil War’s first call for black soldiers and the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment was formed. While their formation was a matter of controversy, Andrew was committed and believed that black men were capable of leadership. Others felt that commissioning blacks as officers was simply too controversial. Robert Gould Shaw, a young white officer from a prominent Boston family, volunteered for the Regiment’s command.

By the time the 54th Infantry headed off to training camp two weeks later, more than 1,000 men had volunteered. Many came from other states, such as New York, Indiana, and Ohio; some even came from Canada. One-quarter of the volunteers came from slave states and the Caribbean. Fathers and sons, some as young as 16, enlisted together. The most famous enlistees were Charles and Lewis Douglass, two sons of famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Shaw and his commissioned officers were white and the enlisted men black; black officers up to the rank of lieutenant were non-commissioned and reached their positions by moving up through the ranks. They trained in Readville, now the Hyde Park neighborhood of Boston.

By the time the 54th Infantry headed off to training camp two weeks later, more than 1,000 men had volunteered. Many came from other states, such as New York, Indiana, and Ohio; some even came from Canada. One-quarter of the volunteers came from slave states and the Caribbean. Fathers and sons, some as young as 16, enlisted together. The most famous enlistees were Charles and Lewis Douglass, two sons of famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Shaw and his commissioned officers were white and the enlisted men black; black officers up to the rank of lieutenant were non-commissioned and reached their positions by moving up through the ranks. They trained in Readville, now the Hyde Park neighborhood of Boston.

On May 28, 1863, upon the presentation of the 54th’s colors by the governor and a parade through the streets of Boston, thousands lined the streets to see this experimental unit off, including anti-slavery advocates William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, and Douglass. The regiment then departed Boston on the transport De Molay for the coast of South Carolina. Colonel Shaw and his troops landed at Hilton Head on June 3 and were soon forced to execute a destructive raid in Georgia. The colonel wrote General George Strong and argued that his troops had come South to fight for freedom and justice, not to destroy undefended towns with no military significance. He asked if the 54th might lead the next Union charge on the battlefield.

While they fought to end slavery in the Confederacy, the 54th also were fighting another injustice. The U.S. Army paid black soldiers $10 a week; white soldiers got $3 more. In protest, the entire regiment — soldiers and officers alike — refused to accept their wages until black and white soldiers earned equal pay, which did not happen until the war was almost over.

On July 18, 1863, the 54th Massachusetts became famous for leading an assault on Fort Wagner, which guarded the Port of Charleston. Shaw led 600 of his men over Wagner’s fortified walls. Unfortunately, Union generals had miscalculated and 1,700 Confederate soldiers were ready for battle. Outgunned and outnumbered, nearly 300 of the charging soldiers were killed, wounded or captured. Shaw himself was shot on his way over the wall and died instantly. Sergeant William Carney of New Bedford was wounded three times in saving the American flag from Confederate capture. Carney’s bravery earned him the distinction of becoming the first African American to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. The 54th lost the battle at Fort Wagner, but they did a great deal of damage there. Confederate troops abandoned the fort soon afterward. For the next two years, the regiment participated in a series of successful siege operations in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, before returning to Boston in September 1865.

On Memorial Day 1897, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens unveiled a memorial to the 54th Massachusetts at the same spot on the Boston Common where the regiment had begun its march to war 34 years before. The high-relief bronze memorial to Colonel Shaw and the 54th Regiment was erected across from the Massachusetts State House through a fund established by Joshua B. Smith, a self-emancipated man from North Carolina. Smith was a caterer, former employee of the Shaw household, and a state representative from Cambridge. Among other tributes, a photographic reproduction of the 54th’s saved national flag is on display in the State House’s Hall of Flags and the 1989 film “Glory,” which won three Academy Awards, brought the story of the Assault on Fort Wagner to viewers worldwide.

BOSTON’S FREE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY

“We can get at the throat of treason and slavery through the State of Massachusetts. She was first in the War of Independence; first to break the chains of her slaves; first to make the black man equal before the law; first to admit colored children to her common schools… You know her patriotic governor, and you know Charles Sumner. I need not add more. Massachusetts now welcomes you as her soldiers.”

-Frederick Douglass. “Men of Color to Arms!” 1863.

It is not an accident that the 54th Massachusetts formed in Boston. In the decades prior to the American Civil War, Boston’s free African American community spearheaded a social revolution, leading the city and the nation in the struggle against slavery and injustice. Key leaders, such as Lewis Hayden, proved instrumental in the formation of the 54th and the African Meeting House, the center of Boston’s free African American community, served as a major recruitment post for the regiment. To learn more about this neighborhood, and the critical events in the decades prior to the Civil War, please explore the resources below.

Tucked away off today’s Joy Street in Beacon Hill, Smith Court served as a center for Boston’s African American community in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Explore how the Smith Court community contributed to both local and national history.

Maritime Underground Railroad in Boston

The powerful stories of freedom seekers escaping enslavement by stowing away on ships, and those that helped them in Boston.

A Man Kidnapped! The Rendition of Anthony Burns

This film explores the story of the rendition of Anthony Burns, a twenty-year-old freedom seeker arrested in 1854 under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law in Boston.

Fighting for Freedom: Lewis Hayden and the Underground Railroad

This 18-minute film, sponsored in part by the National Park Service Network to Freedom, details the life and accomplishments of Lewis Hayden. Lewis Hayden was born enslaved in Kentucky and escaped with his family on the Underground Railroad. He settled in Boston and became one of the most active fighters for freedom in the abolition movement.

VIEW THE INTERPRETIVE SIGNAGE SURROUNDING THE SHAW 54th MEMORIAL

The Partnership to Renew the Shaw 54th Memorial invites the Greater Boston community to view the 900 feet of interpretive signage installed along the construction fencing, revealing the story of the Civil War, the 54th Regiment, and the Memorial that commemorates it.