The Boston Massacre Memorial was dedicated near the Tremont Street Mall on Boston Common in 1888, honoring Crispus Attucks and the other victims of the March 5, 1770 Boston Massacre.

The Boston Massacre Memorial was dedicated near the Tremont Street Mall on Boston Common in 1888, honoring Crispus Attucks and the other victims of the March 5, 1770 Boston Massacre.

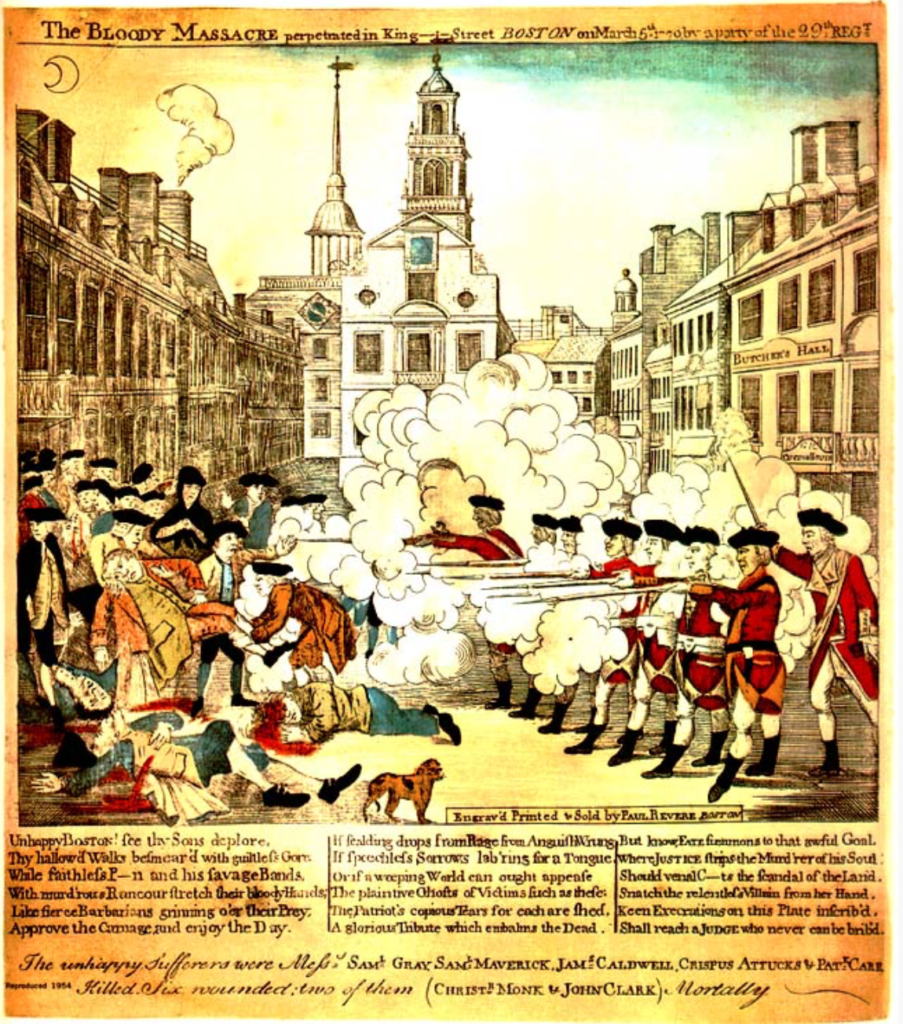

The work of Robert Kraus, the memorial is a standing bronze figure of the Revolution breaking the chains of tyranny and crushing the crown of the British monarch under her foot. The bas-relief bronze plaque is taken from a famous engraving by Paul Revere and depicts the events near what is now known as the Old State House. The frieze shows Attucks lying in the foreground, the first to die.

Who was Crispus Attucks, what is his place, and what was the status of African Americans in the early American historical narrative?

There is little about his life that we can know with certainty, but the most widely accepted understanding is that he was born around 1723 near Natick, Massachusetts. At that time, Natick was a “praying town,” the first of the Christian Indigenous communities set up by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Praying towns were developed by the Puritans in an effort to convert the local Native American tribes to Christianity. Crispus Attucks was likely of African and Native American ancestry; his mother was thought to belong to the Wampanoag tribe and his father was an enslaved African. Through his mother, he may have been a descendant of John Attucks, an Indigenous American who lived in the 1660s. John Attucks converted to Christianity, but during King Philip’s War, sided with his people. He was executed for treason after being captured by the New England colonists.

Crispus Attucks was an enslaved man, considered the property of William Brown of Framingham for 27 years. He liberated himself in 1750 and went to sea, as seafaring was one of the few occupations open to free men of color. Thought to be well over six feet tall, he worked as a sailor on whalers and as a ropemaker between voyages, until the fateful events of March 5, 1770.

In the late 1760s, tensions were high in Boston. The British Parliament passed the hated Townshend Acts placing an indirect tax on glass, lead, paints, paper, and tea, all of which had to be imported from Britain. Anger over the tariffs, forced impressment of sailors, and a boycott of taxed goods led working-class civilians and British soldiers to clash repeatedly.

Historians agree that the Boston Massacre was a critical point in the growing resentment of the colonists towards the British government. No one knows exactly what kicked off the scene on March 5, but Attucks was part of an aggrieved civilian mob that confronted a group of British soldiers outside the King Street Custom House in Dock Square. A rabblerousing group of dockworkers, immigrants, and sailors attacked the group of British guards with rocks, chunks of ice, and clubs.

Hugh Montgomery was the first British soldier to fire. He was identified by witnesses as the man who shot and killed Attucks, making Crispus Attucks the first colonist to be killed by British soldier. He became the first martyr for liberty that day. Three other colonists were also killed. Samuel Maverick, Samuel Gray and James Caldwell were buried with Attucks in a single grave at the Granary Burying Ground, despite prevailing laws regarding segregated burials. Injured Patrick Carr succumbed to his wounds a week later and he was placed in the same grave. Months later, the soldiers were tried for murder, memorably defended by future president John Adams. All were acquitted, with two convicted of the lesser charge of manslaughter.

Colonist-led insurrections were common in the decade leading up to the Revolution. Crispus Attucks was one of the many who played a role in moving angry colonists toward their unprecedented struggle for independence. He is remembered for being the first colonist killed by the British, a seminal moment in a fledgling nation’s collective memory. The American Revolutionaries used the story of the massacre and its victims to advance their political agenda, with the victims as respectable, innocent citizens killed by a cruel and despotic military power. While a disorderly riot was likely a more apt description, it became a key event in forging colonial unity.

The story of Crispus Attucks was embraced and elevated by abolitionists in the 1850s and his memory became a focal point for African American calls for citizenship, inclusion, and equality. In 1851, Black leaders William Cooper Nell, Charles Redmond, Lewis Hayden, and Joshua B. Smith petitioned the Massachusetts legislature for a monument in honor of Crispus Attucks. Black abolitionists inaugurated March 5 as “Crispus Attucks Day” in 1858. Later, during the Civil War, Lewis Hayden would become a recruiter for the 54th Massachusetts Regiment of the United States Colored Troops, and Joshua Smith would play a critical role in persuading state officials to commission a memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th Regiment on Boston Common.

The granite and bronze monument to the Boston Massacre was finally erected on the Common in collaboration with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Crispus Attucks has remained a symbol of African American struggle for freedom and equality, a Black hero, and a founding father of America. Attucks, immortalized as “the first to defy, the first to die,” has been lauded as a true martyr, “the first to pour out his blood as a precious libation on the altar of a people’s rights.”